At the heart of “Marius And Jeannette” lies a potential for profundity in the use of its enclosed setting – that of a small court of houses in a poor working-class area of Marseille – and the recurrence of the idea of someone going away from it never to come back. The characters exist as a tight-knit community that defines their ways of seeing life, and they seem intolerant of any notion of escaping from the closed space they live in.

Alas, writer-director Robert Guédiguian never dares to venture forth into the thematic goldmine it has opened for itself, preferring instead to fall back on lazy, safe clichés of one big happy family whose life is full of laughter and happiness, occasionally interrupted by bursts of quarreling but never to the point that anyone gets truly hurt for very long. Nobody ever has to re-examine the way they think their lives because they know before the film is even over that everything will be alright in the end.

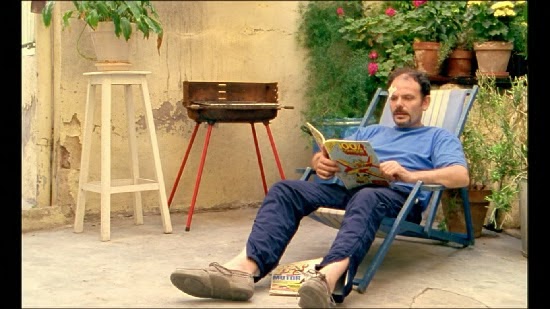

Jeannette (Ariane Ascaride) is a brash, opinionated single mother of two children struggling to make a living as a harried supermarket cashier, whom watchman Marius (Gérard Meylan) catches stealing two cans of paint from an abandoned cement factory. The film’s major shortcoming – that of the characters’ artificiality – is immediately present from that first scene: Everything about the situation, from Jeannette’s exaggerated protests – “Good thing I’m not an Arab or you’d have shot me!” – to the lazy framing, feels as staged as a street performance of Marcel Pagnol’s greatest hits. While Guédiguian’s direction does get better as the two meet again and their relationship progresses, he never does take full advantage of his characters’ confinement to link it with their problems.

The first person to introduce the fear of leaving this place never to return is Jeannette. After unceremoniously kicking him out of her house due to his refusal to say what he wanted from her, she visits him on his worksite as a peace offering and explains that her two children, a white teenage daughter named Magali (Laëtitia Pesenti) and an Arab Muslim son named Malek (Miloud Nacer), come from two different fathers. Magali’s father abandoned them, Malek’s father died in an accident on the construction site he worked at – much like her own father. The idea is entertained further by Magali when she expresses her desire to study journalism in Paris, and compounded later by a drunk Marius when, after revealing the death of his former wife and children as the reason for his increasing malaise with Jeannette and her children, he muses that after a while, once your children leave for school, you start wondering if you’ll ever see them again.

Unfortunately, by that point, it is already too late to rescue the film from its own trite conformism. Marius’s inner struggles, efficiently conveyed by Gérard Meylan, are drowned by unnecessary subplots involving the neighbours. The subplot involving Monique (Frédérique Bonnal) berating her husband Dédé (Jean-Pierre Daroussin) for his lack of involvement in union protests and for having once voted for the right-wing National Front suggests Guédiguian to be less in touch with his character’s background than he’d like his audience to believe, as the FN is currently the first working-class party of France in terms of voters. This is made even more awkward by his ending narration’s dedication of the film to the working class people of Marseille.

Malek’s dual identity crisis – he fasts for Ramadan against his mother’s wishes and does not understand why his mother is Catholic but his father was a Muslim – could have made for an interesting story in the hands of a perceptive writer. Suffocated by his own desire to make his characters be as likeable and suffer as little as possible, Guédiguian can only come up with trite platitudes about all religions being fundamentally alike and God not caring about whether or not you fast or have sex, delivered by resident atheist intellectual Justin (Jacques Boudet) as what are clearly intended to be pearls of wisdom. These scenes go nowhere and achieve nothing but unintentional comedy in the narrator’s epilogue at the end revealing that Malek’s later study of the Quran in its original Arabic confirmed what Justin told him. Unless Malek’s reading were to be strongly influenced by both Justin’s inanities and the communist ideals of his ex-POW lover Caroline (Pascale Roberts), such a conclusion would be highly unlikely at best.

No comments:

Post a Comment